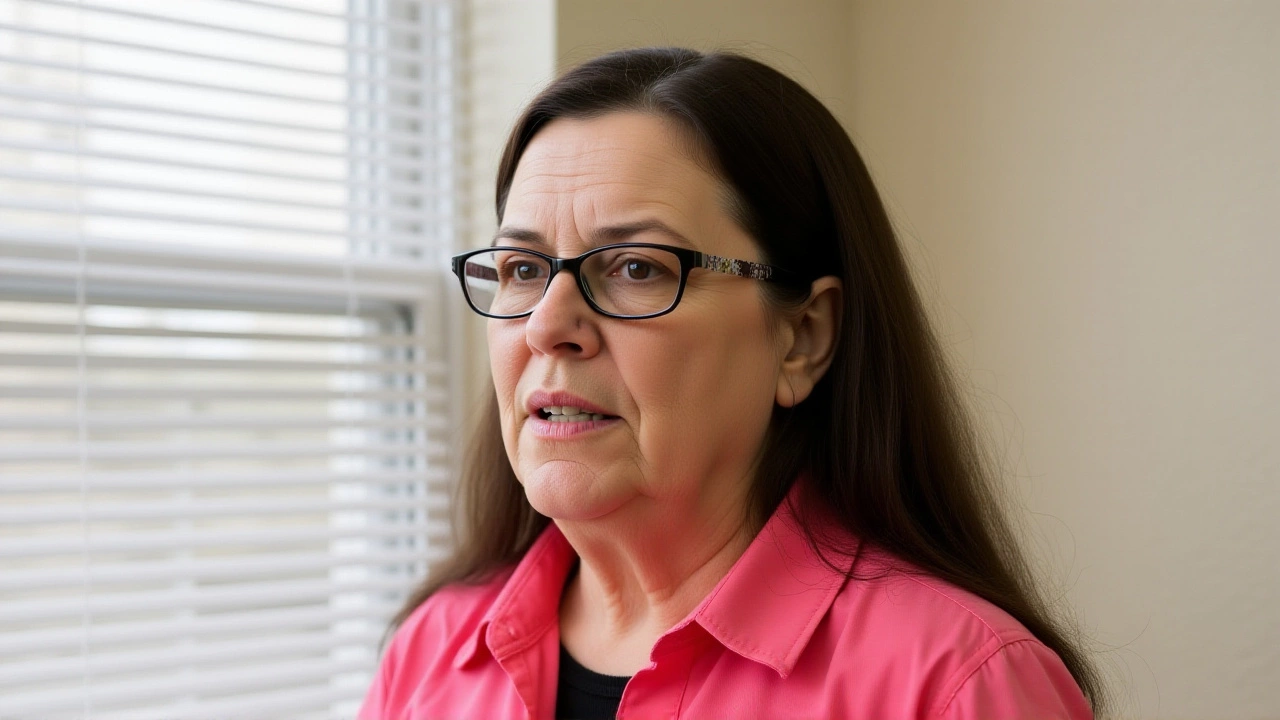

When Kim Davis refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples in 2015, she became a lightning rod in America’s culture wars. Now, nearly a decade later, she’s back in court — this time asking the Supreme Court to reconsider a federal appeals court ruling that upheld her punishment for defying the law. Her petition, filed on July 24, 2025, and docketed as Kim Davis v. David Ermold, et al. (No. 25-125), could reignite the national debate over whether public officials can claim religious exemptions from enforcing Supreme Court rulings — even when those rulings are settled law.

How We Got Here: A Case That Never Really Ended

Kim Davis, then the Rowan County, Kentucky, clerk, gained national infamy in 2015 after the Obergefell v. Hodges decision legalized same-sex marriage nationwide. She refused to issue licenses to anyone — citing her Christian beliefs — and even removed her name and title from the forms. She was jailed for five days for contempt of court. The Kentucky federal district court, followed by the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, consistently ruled that public officials must enforce the law, regardless of personal beliefs. The Sixth Circuit’s March 6, 2025, decision — docketed as No. 24-5524 — reaffirmed that Davis’s actions violated the constitutional rights of couples like David Ermold and his partner, who sued for damages and declaratory relief. Rehearing was denied on April 28, 2025.

What’s unusual isn’t that Davis appealed — it’s that she’s still trying. The Supreme Court has already ruled on this issue. Obergefell v. Hodges is binding precedent. Yet Davis’s legal team argues that lower courts have misapplied the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and that her rights as a government employee were improperly ignored. It’s a legal Hail Mary. But in a political climate where religious liberty claims are increasingly weaponized, the Court may feel compelled to listen.

The Procedural Maze: Waivers, Deadlines, and Whiplash

The docket reads like a legal thriller. After Davis filed her petition on July 24, 2025, the Court set a September 2 deadline for respondents to respond. But on August 4, Ermold’s team filed a waiver — essentially saying, “We don’t need to respond; the law is clear.” That’s common in cases where the petitioner’s claims are legally weak. Yet the Court, for reasons unknown, reversed course on August 7, ordering a formal response by September 8. Then, on August 12, the respondents filed a motion to extend that deadline to October 8. No ruling on that motion has been published.

The case was distributed for the Justices’ private conference on September 29, 2025 — meaning all nine justices reviewed it. But as of November 11, 2025, no order has been issued. That’s not unusual. The Court sometimes takes weeks to release orders. But the silence is telling. If the Court had denied certiorari, it would’ve been a routine, one-line order. The fact that it hasn’t been released yet suggests either internal debate or a delay in processing — or worse, that the Court might be considering granting review.

Why This Matters Beyond Kentucky

This isn’t just about Kim Davis. It’s about whether local officials can pick and choose which laws they enforce. If the Supreme Court takes this case — and lets Davis off the hook — it could open the floodgates. Imagine a county clerk refusing to issue birth certificates to interracial couples. A registrar denying marriage licenses to interfaith couples. A state employee refusing to process transgender name changes. All under the banner of “religious conscience.”

Legal scholars are alarmed. “The Sixth Circuit got it right,” said Professor Elena Martinez of Georgetown Law. “The Constitution doesn’t permit government officials to use their office as a pulpit to deny rights to citizens. If you take the oath, you serve everyone — not just those who match your beliefs.”

But conservative legal groups are cheering Davis on. “This is about the right to live according to your faith without being punished,” said Mark Henderson of the Alliance Defending Freedom. “If you can jail someone for refusing to sign a piece of paper because of their religion, where does it end?”

What’s Next? The Court’s Silence Speaks Volumes

The Court’s next move is the only thing left to watch. If it denies certiorari — as most expect — Davis’s legal fight ends. The Sixth Circuit’s ruling stands. The couples who sued win. The precedent holds. But if the Court grants review? That’s when things get dangerous.

There’s precedent for this. In 2018, the Court took Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, a case involving a baker who refused to make a wedding cake for a same-sex couple. It ruled narrowly, avoiding a sweeping decision. But the optics were clear: the Court was sympathetic to religious objections. If the current Court, with its 6-3 conservative majority, takes Davis’s case, they might not just overturn the Sixth Circuit — they might redefine the limits of religious freedom in public office.

For now, the docket is quiet. The paperwork is filed. The conference has happened. The world waits.

Background: The Original Battle

Kim Davis’s 2015 defiance came just weeks after Obergefell v. Hodges. She was one of the last public officials in the U.S. to refuse compliance. Her case was never about paperwork — it was about symbolism. She turned her office into a protest site. Supporters brought food. Protesters held signs. The media descended. Her story was covered by every major outlet, from CNN to Fox News. She became a hero to some, a bigot to others.

But here’s what’s often forgotten: Davis didn’t just refuse to issue licenses. She ordered her deputies to stop issuing them too. That’s what made it a federal civil rights violation — she was using state power to deny constitutional rights. The courts didn’t punish her for believing. They punished her for acting on that belief in her official capacity.

Her 2025 petition doesn’t dispute those facts. Instead, it argues that the damages awarded to Ermold and others were excessive and that her First Amendment rights were infringed. But the lower courts have already ruled: you can believe what you want. You just can’t use your job to deny others their rights.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Kim Davis still refuse to issue marriage licenses if the Supreme Court takes her case?

No. Even if the Supreme Court grants review, Davis cannot resume refusing licenses. The underlying legal obligation to issue marriage licenses to all qualified couples remains in effect under Obergefell v. Hodges. Any attempt to block issuance would trigger immediate contempt proceedings. The Court’s review would only determine whether she should be held liable for past actions, not whether she can continue to defy the law.

Why did the Supreme Court ask for a response after the respondents waived it?

The Court sometimes requests responses even when respondents waive them — often because a justice has flagged the case as potentially significant. In this instance, the Court may have been concerned that the waiver didn’t fully address the novel legal arguments Davis raised about RFRA and government employment rights. It’s a sign the Court is taking the petition more seriously than it initially appeared.

Who are the other respondents listed as ‘et al.’?

The ‘et al.’ refers to other same-sex couples who sued Davis alongside David Ermold, including couples from Rowan County who were denied marriage licenses between 2015 and 2016. Their names aren’t listed in the docket for privacy, but court records from the original district court case show at least five additional plaintiffs. They’re seeking damages for emotional distress and the cost of obtaining licenses elsewhere.

What’s the likelihood the Supreme Court will hear this case?

The odds are low — fewer than 1% of cert petitions are granted. But this isn’t a typical case. With a conservative supermajority and recent rulings favoring religious exemptions in 303 Creative and Carson v. Makin, the Court may see this as an opportunity to expand religious rights in government roles. Still, most legal analysts believe the Court will deny review to avoid reopening a settled constitutional issue.

What happens if the Court denies certiorari?

The Sixth Circuit’s ruling becomes final. Kim Davis remains liable for damages awarded to the plaintiffs, and her legal team cannot appeal further. More importantly, the precedent that public officials must enforce constitutional rights regardless of personal beliefs remains intact. It would be a quiet but powerful reaffirmation of the rule of law — and a reminder that no one is above it.

Is this case related to other religious exemption cases currently before the Court?

Not directly. But it’s part of a broader trend. The Court has recently expanded religious exemptions in education, healthcare, and business settings. Davis’s case is unique because it involves a government official using public power to deny services — a line the Court has historically been reluctant to cross. If the Court takes this case, it could signal a major shift in how it balances religious liberty against equal protection.